(Excerpts from the manuscript of the book with the same title published in 2018)

The presidency is a matter of destiny.

We heard this often from the man whose destiny actually led him into it.

But there was nothing to indicate he prepared for it.

All that then Davao City Mayor Rodrigo Duterte – Rody or Digong to many- wanted was for the Mindanao agenda to become part of the national discourse in the 2016 presidential election.

Duterte had been raising the red flag and warning that the collapse of the lamented proposed Bangsamoro Basic Law could plunge the country’s second biggest island into a new round of violence.

And so, he started to make the rounds throughout the country positing that federalism may be the best way out of the violent extremism in parts of Mindanao and to spread development and share the nation’s wealth across the archipelago.

He likewise warned that the country had already degenerated into a narco-state. The drug problem, he emphatically pointed out, had become a national security threat.

The Davao City mayor felt none of the presidential contenders showed genuine concern for Mindanao nor did they offer concrete solution to its decades-old problems.

Duterte began the campaign for a shift in the form of government.

The Davao City mayor started his federalism drive in January 2015 in Butuan City determined to draw attention for Mindanao which had always been neglected by the national government.

He made more forays into different cities in Mindanao such as Zamboanga, Pagadian, Valencia, Marawi, Cotabato and San Francisco.

Many listened to and agreed with him.

But he was also being swarmed and swept by the agenda of people who came to listen to him.

In truth, his forays began, whetted, and only precipitated the burgeoning clamor for his own candidacy as none among the presidential front-runners even took notice of the issues he raised.

He was a novelty. A whiff of fresh air espousing agenda few others would even dare talk in whispers.

The people were fascinated with him and began to see him as a viable entrant to the presidential race.

In his late night appearance in a Tina Monzon-Palma television talk show in 2015, Duterte explained his surge as a presidential hopeful as a protest vote phenomenon rather than full endorsement of him. People have grown tired of different sets of politicians parroting the same campaign agenda and just promising to be better than the others.

People who closely followed his steady rise however said his ability to connect with and speak the language of the masses have endeared him to the voting public.

Duterte offered a different perspective and agenda to the presidency and more.

But Duterte had always been categorical about his refusal to run, citing the same reasons over and over again: he was too old, his family was against it, he did not have the resources, and he did not have the nationwide political machinery.

He also did what no other politician even considered doing: campaign against himself – confessing to be a man who has several women in his life – and spicing his discourses with curses and epitaphs perhaps in an effort to frighten people away from him.

But the more Duterte continued his refusal and attempt to be self-effacing, the louder the public noise and clamor became for him to run.

It turned into a classic battle between Duterte the campaigner, ironically against himself, and Duterte the candidate.

In the end, Duterte the candidate was simply too much to resist and overwhelmed Duterte the campaigner.

The inevitable cometh

The road to his candidacy was nevertheless fraught with many twists and turns.

Just as everybody thought he was running, Duterte denied — on at least three formal occasions – that he was interested in the presidency, the last of these declarations mere four days before the October 16, 2015 deadline for the filing of certificates of candidacies.

On October 12, 2015, before a throng of local news reporters and correspondents in Davao City, Duterte held back his tears as he read a statement categorically stating he is not running for president.

He said his daughter Sara wrote him a letter almost begging him not to run.

“You owe them nothing,” he quoted the last paragraph of Sara’s letter to him.

His voice cracking, Duterte said he will fade into retirement if Sara would agree to run for city mayor.

“The country does not need me. I find no need for it (the presidency),” Duterte tersely said inside a jam packed room at the Grand Men Seng Hotel.

For the very accomplished mayor of Davao City who reigned for 23 years, there were no more mountains to climb, no accolades to run after.

Still many kept their hopes up.

After all, from virtually a non-entity in the presidential derby, he barged into the March 2015 Pulse Asia survey for presidential contenders.

A year before, he was not even in the conversation.

In that May 2015 Pulse survey, 7.6 percent of respondents polled said they would vote for the maverick Davao City mayor.

By mid-September of that year, a week after he held the second of three press conferences to deny any plans to run for president, his poll rating went up to 16 percent according to Pulse Asia, good enough for fourth in what turned out to be a 5-way race early on.

But it was still a no go for the presidency for Duterte, prompting close aide Christopher ‘Bong’ Go to wear a T-shirt emblazoned with ‘No is No’ statement.

Still, his growing legion of supporters kept their hopes alive and waited for a miracle that will change the mind of the Davao City mayor.

Duterte would eventually break the hearts of his supporters past the October 16, 2015 deadline for the filing of certificates of candidacies.

He did not show up at the Commission on Election office even if as early as a day before, his supporters had already camped out in front of the poll body building in Intramuros, Manila.

Instead, Duterte filed his certificate of candidacy seeking re-election as Davao City mayor after Sara had declined a return into the top post in Davao City, which she left in 2013 so that her father could come back at City Hall.

When it became obvious that his well-awaited arrival at the Comelec office would not materialize, his supporters scrambled for a desperate shot and asked PDP-Laban member Martin Diño to file his certificate of candidacy just to beat the deadline.

The Diño certificate of candidacy contained errors which other candidates later sought to declare null and void when its providential time came.

For Duterte’s small group of loyal supporters who joined him in the ‘listening tour’ that ended up with him becoming a force in the presidential race, the Comelec debacle was a lowest point in the journey of the Davao City mayor that defined his destiny.

Led by longtime aide and political strategist Leoncio Evasco Jr, they retreated into a room inside the Manila Hotel, unable to face both the chorus of heart-broken believers and the hecklers who thought it was the end of a fantasy.

With Duterte out of the presidential race, the rest of the candidates felt a thorn had been removed from their throats and a potential threat eliminated from the vote-rich Mindanao islands.

Their celebration turned out to be premature and short lived, though.

Duterte would engineer one of the most bizarre turn of events in Philippine politics and turn the history of the presidential election into one of the most dramatic, unorthodox, and unpredictable presidential campaigns ever.

As pressure from friends, supporters, and people from ordinary walks of life across the country continued to build up even after the October 2015 Comelec deadline, Duterte finally caved in.

After securing the support of his family and a relenting message from daughter Sara who shaved her head in support of him, Duterte was ready to throw his hat into the presidential derby.

At the birthday of his friend Fred Lim in Cavite on November 22, 2016, Duterte announced he would be running for president and would substitute for Michael Diño as the standard bearer of PDP-Laban, a party founded in Mindanao by Aquilino Pimental Jr., a Mindanaoan like him.

In between his first press conference in August and his decision to run, Duterte generated tremendous national exposure that he was already running fourth among the presidential contenders in many surveys.

It was unplanned and uncharted but it was a combined stroke of political genius and luck to be able to land in the front pages and in primetime television without spending a single centavo, and yet becoming the hot copy; while his opponents have already invested and hired topnotch public relations firms, some foreign.

On November 27, 2015, five days after announcing his candidacy for president, his legal team led by longtime friend Salvador Medialdea appeared before the Commission on Elections to file his certificate of candidacy vice Diño.

Mayor Rody woke up earlier than usual that day and personally headed to the Comelec office in Davao to withdraw his COC for mayor. With him was daughter Sara Duterte-Carpio, who in turn filed her own COC as her father’s substitute.

True to form, he did it without much fanfare. Rather than appear at the Comelec Central Office, he chose his legal team to do the honors of filing his substitute certificate.

As soon as the substitution was completed in Davao City, a group headed by now Executive Secretary Salvador Medialdea filed Duterte’s COC for president at the Comelec’s head office in Intramuros.

Medialdea was armed with a special power of attorney that Duterte confirmed later in a personal visit to the Comelec.

Unlike October 16, November 27 came swiftly. No one from the press knew about it until it was over.

That dramatic event made him an even bigger and hotter copy for the day’s headlines as reporters sought to find him.

Desperate, his opponents questioned the substitution process citing infirmities in the certificate of candidacy filed by Diño.

The Comelec however ruled in favor of the Davao City mayor.

So the race began.

On January 6-7, 2016, his supporters held their first organizational meeting, launching the campaign team that would trail blaze across the country, building momentum and a spectacular crescendo unseen in the history of Philippine presidential elections.

That team had its first taste of what it will take to run a presidential campaign when it went in full complement in General Santos City on January 16.

A few days later, on January 20, he appeared before young La Salle students in what was supposed to be a forum for presidential candidates. No other candidate appeared giving Duterte the platform to espouse his campaign agenda all by himself and running mate Senator Allan Cayetano.

The opponents ignored the town hall type meetings and discussions. They would pay the price later as these started Duterte’s magnificent campaign narrative.

For him, it did not matter how big or small or how near or far, Duterte will reach out and be where the crowd was willing to listen to him.

Duterte packaged himself as the candidate of the people.

Early bird

If Duterte was the last to confirm his entry into the presidential race, he was the first to hit the road running.

At the stroke of the first minute of February 9, 2016, the first day of the presidential campaign period, Duterte’s team was already strategically positioned in the urban community of Delpan in Tondo.

Less than 30 minutes after, while other presidential candidates were sound asleep and in deep slumber, Duterte broke bread and ate the quintessential breakfast meal of Filipino households – a fare of salted egg, pancit, and pandesal.

Later in the evening, he was in Tondo, in the middle of an intersection. It was the first of his rallies that spilled into the wee hours of the following morning.

Those opening salvos were powerful images and the messages they delivered became the narrative throughout the campaign.

He campaigned on the platform of anti-drug, anti-corruption, and anti-crime agenda.

He was dogged, adamant, and unrelenting.

He bared all and even more.

But every time, he went back to his agenda – drugs, crime and corruption.

Duterte laced his long winding speeches with expletives, foul languages, sexist jokes and sick scenarios, and a mouthful of history — traits and scare tactics that were unheard of and never ever seen before from a presidential candidate.

He was every PR man’s worst nightmare in terms of packaging a wholesome candidate.

Yet, he was his own powerful walking billboard and effective spokesman.

More than anything, the people were regaled and amused. They saw something different in the man from the south who packaged himself as one of them.

They came to hear him speak their frustrations and their dreams in their language.

A group of women, largely based in Mindanao, were unperturbed by his off-tangent anecdotes and verbal slur on women and even formed their own support group – the FORWARD – Forum of Women for Action with Rodrigo Duterte.

At the onset of the campaign period, his sorties were media events because of the novelty.

He was the most quotable and unorthodox among the presidential candidates.

As the campaign wore on, Duterte the unknown entity became the huge political celebrity

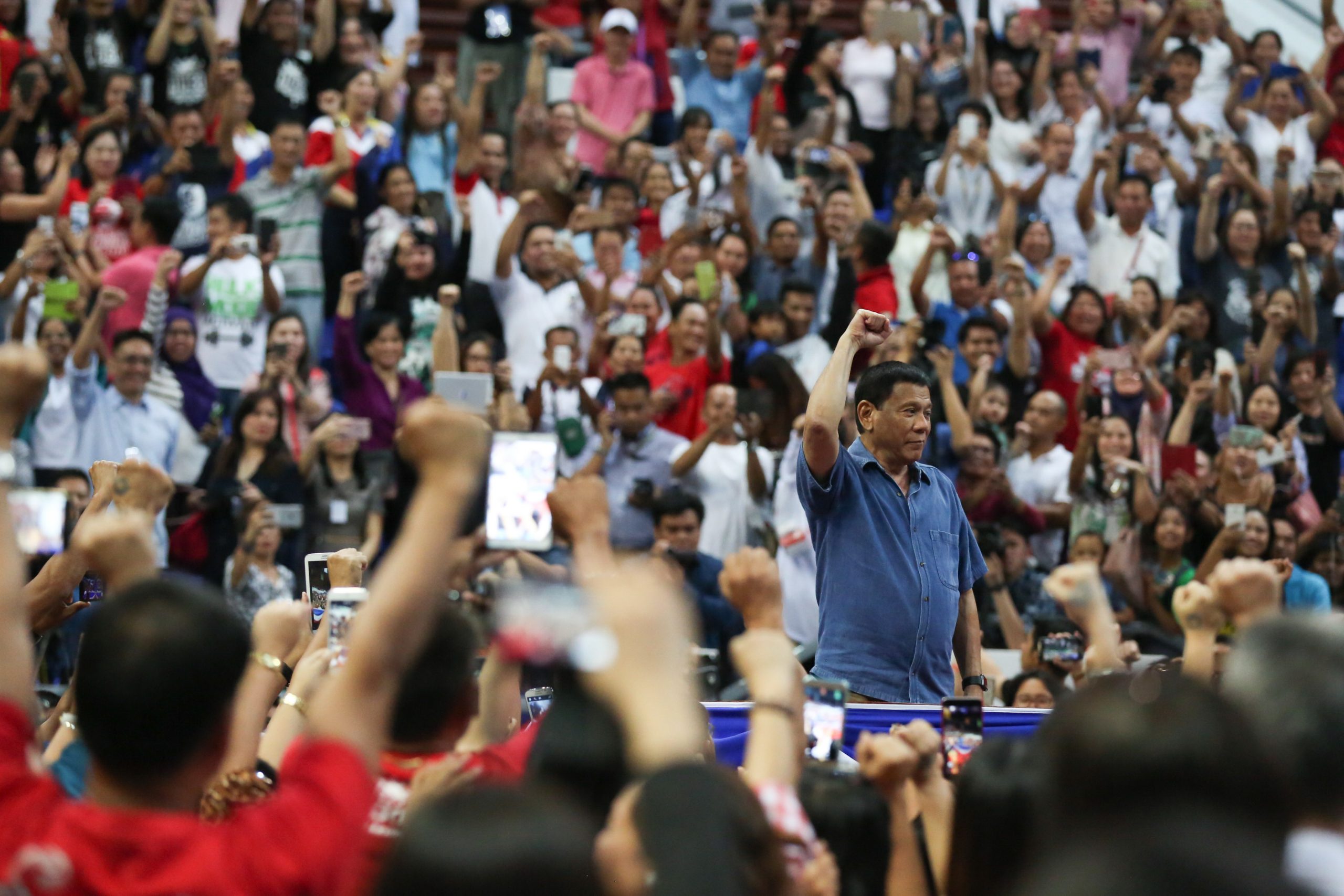

The crowd attending his rallies began to grow bigger, more animated and spiritedly engaged.

Everywhere he went, Duterte never failed to attract the crowd, many braving the heat, squeezing their way into the tight spaces, and staying late during rallies that were turning into mammoth gatherings.

Mayor Duterte’s ability to blend, listen, converse, mingle, empathize, and humor effortlessly with whoever was in front of him endeared the maverick candidate across the social strata of the Filipino electorate.

He rose steadily on the side of popular awareness.

Shifting momentum

By the middle of the 120-day campaign period, Duterte saw his poll ranking climbed from fourth at the beginning of campaign period to a statistical tie with survey frontrunner Grace Poe.

He would top all poll surveys for voters’ preference by the end of March, a lead he would not relinquish on his march to victory.

He did so while holding fort and showcasing his best during the three presidential debates, which further separated him from the rest of the presidential candidates.

Soon, the focus of attacks and black propaganda would shift towards and on him.

He became the object of incessant, vile and vitriolic attacks. He was scored as uncouth, masochist, maniacal, and a murderer unworthy of the people’s vote.

They pounced on his rape jokes and accused him of keeping an undeclared and hidden wealth.

He would weather the attacks all away and emerge even more popular.

But not a few among his circle of campaigners were caught by surprise and thrown off guard by his unpredictable adlibs in otherwise predictable campaign speeches.

Many tried but failed to steer him away from controversy.

When he captured the lead, they tried to protect and insulate him.

But Duterte stayed his course.

He was, after all, his own man.

Duterte, now the frontrunner, refused to slow down and continued with what he was good and best at – he spoke his mind and heart out with calculated abandon.

March to victory

The Duterte bandwagon and phenomenon reached a feverish high in the days heading to election day.

Each sortie became a march towards victory culminating into a humongous miting de avance at the famed Luneta Park where more than a million enthusiastic crowd turned out to hear the front runner speak.

Before the Luneta rally, it was only Duterte’s group of videographers who consistently aired the swollen crowd that attended his political assemblies. The Luneta rally was too big to ignore, the mainstream media just had to cover it.

But that wasn’t how it was as he was gathering momentum. From being the media favorite pre-campaign period, media coverage became less permissive as the crowd built up and the ratings rose.

So his campaign team produced alternative images and videos that took social media by storm.

These powerful images and pictures – especially the drone aerial shots – kept his supporters abreast of the pace and crescendo the Duterte campaign team was engineering.

Duterte was also the first candidate who maximized to the full extent the emerging and influential social media force.

His team of tech-savvy social media army steered the tens of thousands of netizens into one of the most animated and engaged network of supporters, many of them oversees Filipino workers (OFWs).

Limited by Comelec prohibition on paid airtime for candidates and driven by their quest for revenues, television stations shunned away from airing and showing the big crowds during his sorties.

Instead they nitpicked and chose to capture sound bites that Duterte regularly spewed.

They frantically tried to derail the 4 o’clock Duterte bullet train.

They tried in vain.

The throng of Duterte supporters who trooped to the Luneta was the biggest of its kind in the history of the presidential election.

The mass of people began assembling at past noon on May 7, the last day of the 2016 presidential campaign period.

A huge Philippine flag, which first appeared in Olongapo City, came out at past 3 o’clock in the afternoon. It would become a permanent fixture of the night’s rally until it was folded at past 11 in the evening.

Crowd estimate was at a low of 750,000 to a high of 1.2 million. It was the biggest crowd to attend a political rally by any presidential candidate — ever.

To say it was a madding crowd was an understatement.

The mood quickly shifted from gregarious to victorious.

The smell of victory was all over the air by the time Duterte was handed the microphone.

For all who stuck and stood by him throughout, the May 7, 2016 miting de avance was a fitting end to a battle fought hard, which began in the south, where no one expected them to win and gave them serious notice.

The verdict

If the Luneta rally was festive and celebratory, the next 48 hours were tense and jittery.

Although Duterte was leading by double-digit margins in all surveys ten days before decision day, there was no telling if victory is all but wrapped up.

Duterte appeared before his designated voting precinct at the Daniel R. Aguinaldo National High School on May 9, 2016 at past 3 p.m.

While all in his camp were taut and twitchy, Duterte was relaxed and well rested. He was cool calm and collected.

It took all of 10 minutes for him to cast his ballot, one of the more than 16 million votes that spelled his victory.

Duterte left the voting center amid a throng of supporters.

At 6:30 in the evening of May 9, barely 30 minutes after the counting begun, Duterte was leading all other candidates by a wide margin cornering almost 35 percent of the 5 million ballots counted.

That lead translated into a total of 16,601,997 votes or 39 per cent of the votes cast going for him.

When all was over, he led his next pursuer by a margin of 6,623,822 votes which was good enough for 23 percent.

That margin of victory was the largest ever by any winning candidate in the post-EDSA presidential election.

The verdict came in quick.

It was overwhelming.

And it was decisive.

Before the night ended Duterte’s journey to the presidency ended in sweet victory.